We invite everyone to the forthcoming SPS seminar on 22 of September. Gregory Bracken, who recently joined the Spatial Planning and Strategy section at the Department of Urbanism,will deliver a talk on the Shanghai alleyway house, an endangered generator of street life.

Gregory Bracken (1968) is from Ireland and received his B.Sc. from the Dublin Institute of Technology in 1992 before moving to Asia where he worked as an architect for ten years. He received his M.Sc. and Ph.D. from TU Delft’s Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment (2004 and 2009 respectively) and has recently started working at the Urbanism Department. Previously he was based in the Theory Section of the Architecture Department where he was one of the co-founders of the Footprint journal. From 2009-2015 he was also a Research Fellow at the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS) Leiden where he set up (with Dr Manon Ossewijer) the Urban Knowledge Network Asia (UKNA) with a €1.2 million grant from Marie Curie Actions. His recent publications include Asian Cities: Colonial to Global (Amsterdam University Press, 2015), The Shanghai Alleyway House: A Vanishing Urban Vernacular (Routledge 2013, which was translated into Chinese by the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press in 2015), and Dublin Strolls (The Collins Press, 2016) a bestselling guide to the architecture of Dublin co-written with his sister Audrey Bracken.

Gregory Bracken (1968) is from Ireland and received his B.Sc. from the Dublin Institute of Technology in 1992 before moving to Asia where he worked as an architect for ten years. He received his M.Sc. and Ph.D. from TU Delft’s Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment (2004 and 2009 respectively) and has recently started working at the Urbanism Department. Previously he was based in the Theory Section of the Architecture Department where he was one of the co-founders of the Footprint journal. From 2009-2015 he was also a Research Fellow at the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS) Leiden where he set up (with Dr Manon Ossewijer) the Urban Knowledge Network Asia (UKNA) with a €1.2 million grant from Marie Curie Actions. His recent publications include Asian Cities: Colonial to Global (Amsterdam University Press, 2015), The Shanghai Alleyway House: A Vanishing Urban Vernacular (Routledge 2013, which was translated into Chinese by the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press in 2015), and Dublin Strolls (The Collins Press, 2016) a bestselling guide to the architecture of Dublin co-written with his sister Audrey Bracken..

.

.

The Shanghai Alleyway House

BG West 270, BK, TU Delft, 22 Sept, 13:00

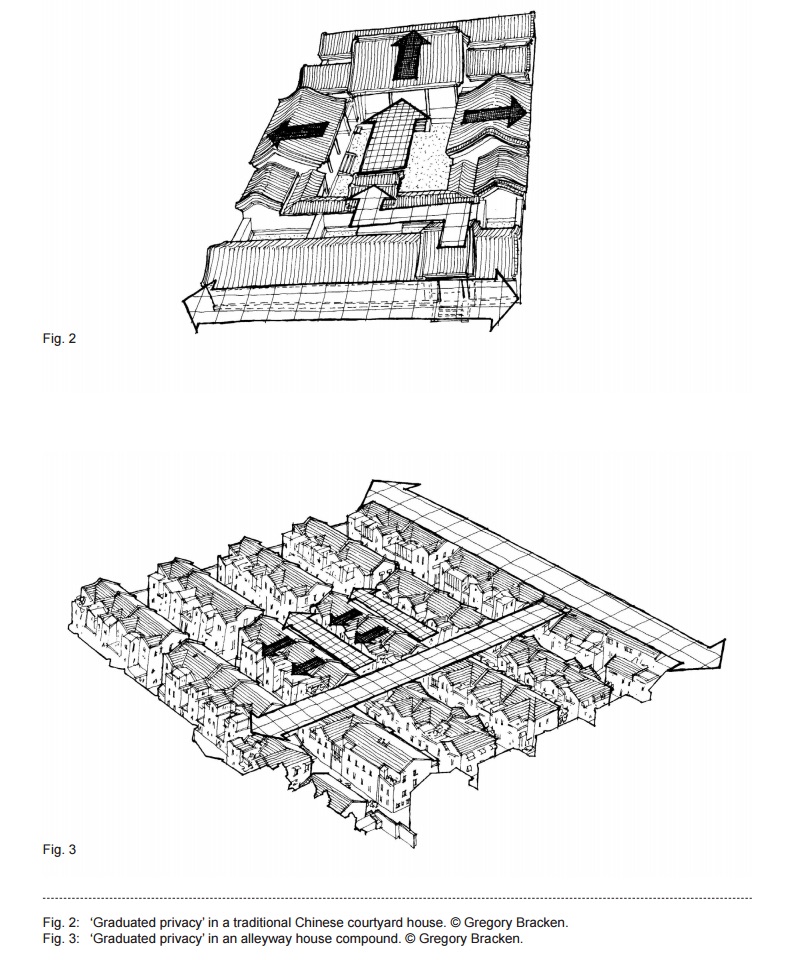

At a time when China was reeling from the humiliation of the ‘unequal treaties’, the city of Shanghai was producing a new and remarkable housing typology: the alleyway house. A nineteenth-century commercial development designed to house the urban poor, most were speculative real-estate ventures and consisted of large blocks, typical of inner-city Shanghai. Divided into three or four smaller blocks, they were accessed by alleyways; the main one being four to five metres wide and running perpendicular to the access street. Larger compounds had smaller alleyways crossing the main one at right angles. Commercial activity was confined to the houses facing onto the boundary streets, although some informal commercial activity also occurred on the main alleyway. Access was via gates, which closed at night.

The alleyway house is known by a variety of names, lilong being the most common, while longtang is the Shanghainese term for it. There is also the shikumen, a particular type of alleyway house which takes its name from the elaborately carved doorway, a throwback to the paifang or ritual gateway found in traditional Chinese cities. The application of Western decoration, and the fact that the houses were built in terraces, has led some to speculate that the alleyway house was somehow a hybrid of Eastern and Western building traditions; there is little evidence to support this view. The builders of the typology may have copied some Western detailing but the alleyway house’s genesis is clearly Chinese. The fact that they were built in terraces is more to do with the fact that this is an efficient use of expensive land, while the multi-storey dwelling, which was generally considered unusual in China, does have a precedent in the shophouses of Guangzhou. Finally, to dispel any notion of similarity with the Western terrace, nearly all of Shanghai’s alleyway houses were built facing the same direction: south, in accordance with the precepts of feng shui, an arrangement unheard of in the West.

The Shanghai alleyway house was a rich and vibrant generator of street life, and was unique to Shanghai. It occupied the ambiguous space between the traditional Chinese courtyard home and the street. The system of ‘graduated privacy’ that obtained within its alleyways ensured a safe and neighbourly place to live – what I have termed a ‘benign panopticon’, where the eyes of the street are friendly ones, looking out for their neighbours. Due to rapid redevelopment in recent decades this once ubiquitous typology is under threat. Recent redevelopments, such as Xintiandi, Jian Ye Li, and Tianzifang, might point the way to the future, but we must not lose sight of the fact that this typology will never again house the people for whom it was originally built, i.e. the urban poor.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The Shanghai Alleyway House: A Vanishing Urban Vernacular (Routledge, 2013)

(Chinese translation, Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press, 2015)

Please follow and like us: